Mon 3 Sep 2012

Relativity

Posted by anaglyph under In The News, Numbers, Philosophy, Politics, Science, Skeptical Thinking, Space, Technology

[26] Comments

While Violet Towne and I were out on our bikes yesterday, our conversation turned to philosophy and politics, as it sometimes does. Specifically, I was defending the Mars Lab/Curiosity program against her assertion that it was a waste of money when there were so many much more important issues on the political plate. Well, I agree that there are numerous pressing matters that need our attention (and money) but I was most vehement that there are a lot of other things that could lose a few pounds (metaphorically speaking) before we should start carving up great and inspiring science projects.

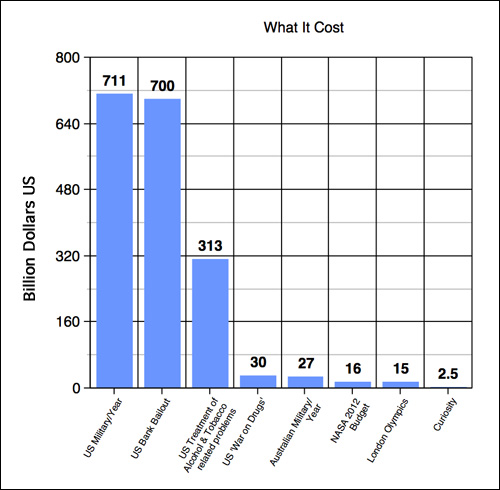

“For instance,” I said, “Do you realise that the 2012 Olympics cost more than twice as much as Curiosity? And that the US bank bailout was more than ten times the budget of the Mars Science Lab mission?”

I don’t think she believed me.

“Show me the numbers!” she said, defiantly.

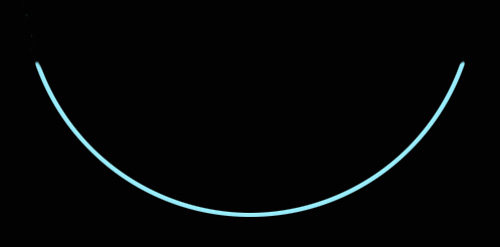

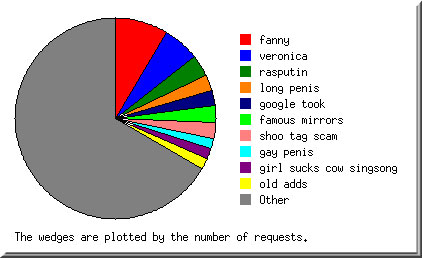

Well, Acowlytes, you all know it’s best not to challenge the Reverend when he’s on his soapbox, even if you’re the Reverend’s wife. ((You’d’ve thought she would have figured this one out by now…)) When we had pedalled homewards, I went straight to Captain Google, and plugged in my questions. You might understand, dear Cowpokes, my utter amazement when I found my figures were wrong. Wrong by an order of magnitude. But not in the direction VT had hoped. It’s FAR worse than I had even imagined. Here ya go. I made a graph:

As you can plainly see, the budget for the Curiosity/Science Lab project is not even one pixel high on this comparison scale.

So, in order to get some perspective on how much that little rover trundling around on the surface of Mars costs, let’s examine some of those figures and related issues. First of all, it’s obvious that the military budget for the US for one year (2012) and the amount of money spent on the bank bailout are each in a completely different league to the kind of expense put aside for Curiosity. It isn’t hard to see that even NASA’s entire budget for 2012 is hardly a blip on the radar for the government accountants when compared to sums like that. What’s even more gobsmacking is that each of these figures (that is, ONE SINGLE YEAR of US military spending, or the humoungous pile of money forked out to save the US economy from the destruction wrought by the excesses of greedy and morally reprehensible assholes) exceeds the budget of NASA’s entire 50 year existence. ((Here. Do the sums.)) The yearly outlay for military air-conditioning alone exceeds NASA’s annual budget by 4 billion dollars. ((The Pentagon rejects this figure, which was calculated by Brigadier General Steven Anderson, a military logician for operations in Iraq. They have, however, not put forward an alternative anywhere I could find. I’m open to correction on this.))

The London Olympics cost, in fact, nearly 6 times more than Curiosity – not merely double as I’d thought – and we’re only talking about the money spent to stage the games. ((Arguably, some of that expense is recouped in benefits of one kind of another by the British taxpayers, but not the majority of it by any means. Equally as arguably, the Mars Science Lab program has benefits of one kind or another for the human race.)) It’s plain that large amounts are poured into the Olympics from elsewhere as well, including every participating nation’s competition expenses, and not insubstantial amounts from all the bids made by countries attempting to secure the Games every four years. That’s a frikkin’ ginormous pile of cash for a sporting event. Even if you amortize the London expense over 4 years, the yearly figure still exceeds that of the Mars Science Lab mission. Of course if we permit that, it should be fair to amortize Curiosity’s cost over the Mars Science Lab program’s lifetime (9 years), making the contrast even greater and returning an expense to the US taxpayers of $277m per year (or, less than a dollar per person per year). For 2012/13 the Australian government has budgeted over 10 times that figure for sport. ((I had trouble finding out how much the US government spends on sport. It’s either a well kept secret, or they don’t care to support the same ridiculous level of sports fantaticism as ours does.))

To put that per-person/per-dollar/per-year expense into perspective, Americans ((Canadians are also included in this figure, but even cutting it by, say, a generous third, that’s still a shitload of money.)) spent 4 times the cost of the Curiosity mission at the cinema in 2010 ((I couldn’t find anything more recent, but I think it’s safe to say that 2011 & 2011 will track that figure.)), and are spending something like $137 billion dollars a year on alcohol ((2002 figures, but I think we can probably assume that has trended upwards rather than down.)) and somewhere in excess of 30 billion dollars a year on cigarettes. In 2011, the US government spent 313 billion dollars ((This is probably a conservative estimate – it’s hard to get an exact figure due to the nature of defining the field, but I’m quoting on the conservative side. Stats here and here.)) on ameliorating the problems caused by the abuse of all that alcohol & tobacco. And, while we’re on the subject of substance abuse, coming in at a staggering 30 billion dollars, ((Depending who you ask. It’s variously quoted at somewhere between 20 and 40 billion. It’s certainly not less than 20, but it may be more than 40. In any case, I’ve erred on the probable side of conservatism and just taken the median.)) America’s so-called ‘War on Drugs’ costs the nation over 10 times the budget of Curiosity (or, nearly twice the annual NASA budget) every year and that is widely argued to be a complete waste of money. ((Here, here, and here, for just three examples of hundreds you can find.))

I could, of course keep going with this – I haven’t touched on gambling, or government inefficiency, or tax breaks for religion or a half dozen other areas where large amounts of money seem to slush around without a proper degree of scrutiny. But what does all this mean, in the end?

For me, it’s simple. As humans we can, of course, choose to put our resources wherever we like. So far, I believe that choice has always leaned far too heavily towards the things at which animals are good – being the fittest, the strongest, the fastest. Or being the greediest, the most aggressive, the most dominant. It has not served us well. The result is that we have become powerful animals facing an existential crisis, and the traits that we carry as animals – the aggression, the greed, the power-mongering – are the exact opposite of what we need to get us out of this crisis. We are starting to encounter problems that we will not conquer by being fast, or strong or fit. ((Or religious.)) Being better at animal things was once enough. Now it isn’t.

The things that humans alone are good at – the things that our brains enable us to do such as imagining the possibilities of the future, pondering the poetry of our existence, turning our curious gaze onto the mechanics of the very universe itself – occupy the very tiniest parts of the minds of most people (and therefore most governments). This ability that humans have to plan for the future by creating a mental vision of it is more-or-less nonexistant in all other animals. ((To all intents and purposes it is completely non-existant as far as we know, but that’s an area of research that is still contentious.)) So what do we do to the people who are very good at this kind of inspirational far-thinking? We vilify and undervalue them. When they tell us ‘There is a big problem with the climate and we should do something about it!’ the powerful apes get up on their boxes and beat their chests, so that they might remain popular and powerful, and the greedy apes use all the cunning that their superior brain has given them to make arguments that everything is OK and we should all just kick back and consume, and the fit and fast apes run around entertaining everyone. If we cannot use the leverage that nature has given us to come to terms with the world-destroying problems we now face, we are truly doomed. We have squandered the one advantage that we have over other animals. Our difference will have enabled us to wipe ourselves out, rather than allowed us to achieve that future which we alone can imagine.

So what has all this to do with a little vehicle pottering around in the dust of a cold world some 225 million kilometers from our home? Well, in my opinion, projects like Curiosity help us turn our gaze outward – out of ourselves and away from our tiny little human preocupations. Indeed, I think that this curiosity to know stuff that has no direct consequence to our animal existence is a marker that says that we may, perhaps, have a chance after all.

There are, of course, many areas where we might have directed the 2.5 billion dollars that went to Curiosity. Violet Towne considered that it would have been better spent going towards helping solve the climate change problem, for example. Well, I agree that climate change research is an area that could really use that kind of money. And there are numerous pressing compassionate issues that are desperately in need of money also. I hope my argument has convinced you (and her), though, that stealing the funds from visionary human endeavours like the Mars Science Lab is entirely the wrong tactic if you want to help address these probems. I want to make it quite clear that I’m not advocating doing away with sport, or stopping everyone from imbibing reality-altering substances, or even saying that we could conveniently curtail all our military spending, but to me it seems that all these pursuits – these profoundly ‘ape-like’ pursuits – are where we should look first for money that could be better off spent elsewhere. I’m pretty sure they could spare a little of the quite exorbitant amounts of cash that are currently rained down on them.

___________________________________________________________________________

Violet Towne fears that I have portrayed her as a Luddite here, and as somewhat anti-science. I want to assure you that she is not, and that I respect her views, and her willingness to challenge me on my own, very much. You all know that it’s unlikely I would last long with a partner who didn’t have a vibrant and informed worldview. But I think I am right in saying that, like many people, she had formed an opinion – almost entirely concocted by irresponsible and ignorant media reporting, in my view – that NASA spends excessive amounts of money on things no-one really cares about. My intent with this post is simply to demonstrate that, in the grand scheme of things, NASA’s budget is relatively well spent. It seems to me that robbing Peter to pay Paul by redistributing NASA’s budget to areas of more pressing need is a kind of madness fanned by a perplexing and distressing anti-science sentiment creeping across the world.