Sat 23 Feb 2013

Binauralaura

Posted by anaglyph under DIY, Gadgets, Geek, Music, Robots, Science, Sound, Technology, Work

[6] Comments

So at last, my mysterious project is complete.

You saw Laura a couple of days ago as she arrived, straight out of the box. She was not quite as perfect as I would have liked, so the first step involved some surgery…

As did the second step. ‘Trust me Laura,’ I said ‘I’m a doctor’. Well, I’m a Reverend, and that’s as good as, right? I mean, with God the Cow on my side, how can I do wrong? A little release of intracranial pressure…

Ah, that’s better. And now for the pièce de résistance… And Binauralaura (Laura to her friends) is ready to begin to listen…

Binauralaura is my new binaural recording rig. Here begins the edumacation part of this post, so those who came for the titillation can now go watch Fox news and eat donuts.

To start, you should know that when you hear a stereo recording of sound or music – pretty much any recording – it is presented to your ear in a very different way to the way in which you actually hear in reality. There are many reasons for this, but the main one is that most sound recordings, and most music recordings in particular, use a somewhat artificial method to render their stereophonic sonic landscape. In a standard electronically-reproduced stereo domain, the stereo image is created from two point sources – your two hifi speakers, or two headphone speakers – each of which is fed by a discrete channel of recorded sound. All sound in a stereo field is thus contained in two separate, but interconnected, recordings – one for left and one for right. In simple terms, if a sound is only in the left channel, it will appear to come from your left. If it is only in the right channel, it will appear to come from your right. In almost all modern recordings, when an engineer wishes to make a sound feel like it is originating elsewhere in the stereo image – slightly left of centre, for instance – it is made slightly louder in the left channel than it is in the right. To make it appear to be right in front of you – or ‘centre’ as we say – then the volume is made exactly equal for both the left and the right channels. For over half a century, this result has been achieved by ‘panning’ the sound on a mixing console. A panner is simply a control that varies the amount of signal (or loudness) added to each channel.

In the real world, though, our ears don’t judge the position of a sound in space solely by its loudness. Certainly, loudness is one aspect of the mechanism, but there are numerous other factors in play. The principal one is a component of time. If you hear a dog barking somewhere ahead of you, and slightly to the left, one of your ears will be receiving a slightly greater sound pressure (loudness) than the other. But crucially, that same ear will be hearing the sound very slightly before your other ear does. The human brain can, in fact, differentiate time differences smaller than 10 microseconds between your two ears, and it is that ability which allows us to aurally locate objects in space with an accuracy of about 1 degree. ((It’s more accurate if the sound is in front of you. As it approaches the extreme sides, the ability to pinpoint its location decreases.)) ((As an aside, there is a species of fly which is so small that its ears are too close together for its head to have any effect on time delays between them. Instead, it has evolved an entirely different and novel way of localizing sound. The trick it uses (its ears are physically coupled together, allowing it to detect sub-microsecond delays) is currently being explored as a possible microphonic technique.)) Up until very recently, this time component could not be easily recreated in a studio mixing environment, and since – like most things – the recording process is a trade-off between the achievement of perfection and economic imperative, the old panning paradigm is still alive and well (and dominant) in modern sound mixing facilities. I would make a rough guess that 99.9% of all music and sound you hear is rendered to stereo with crude analogue panning.

Now, some of you may be ahead of me slightly here, and interject: ‘But Reverend, what about a recording made solely with two microphones? There’s no mixing console involved there (so no artificial panning) and the sound of any object off centre to the microphones must arrive at slightly different times for each? Surely that’s preserved in a recording?’

Well, yes indeed. Two separate microphones (or a coincident stereo pair, to use the lingo) will indeed preserve the delay times inherent in the scene being recorded but they still don’t hear the world like our ears do.

The important thing to understand at this point is that when it comes to human hearing, our eardrums – our ‘microphones’ if you like – are only part of the story. There are several other key players in the process, the most important of which is our brain. Our brain and ears work together to ‘hear’ the world, and the way we hear is a lot more complex and clever than you probably ever stopped to think about.

One thing that every one of us knows (because our brain figures it out pretty much as soon as we are born) is that our ears are separated from one another by a head. Everything we experience in the realm of natural hearing is mitigated by this big noggin right in the middle of things. And our brain calculates our aural experience by taking it into account as it forms our sonic picture of the world. Likewise, we are accustomed to hearing our surroundings via two fleshy reflectors that funnel the sound toward the vibrating membranes that actually detect the sound waves. The complicated contours of our ears – the pinnae – don’t simply look like they do for decoration. The whorls and cavities of the ear surface impose certain kinds of characteristics on the sound that reaches them, and these help us with sound localisation, and, to a certain extent, with the perception of fidelity.

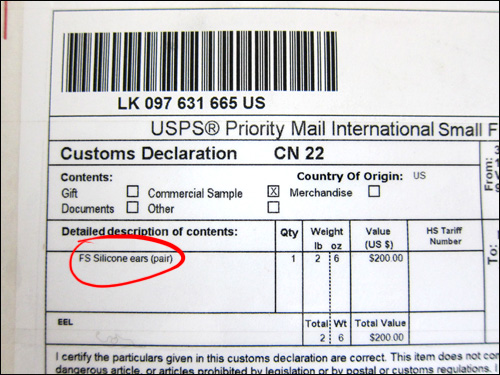

Which brings me all the way back to Binauralaura. Laura’s head contains a pair of high fidelity omnidirectional microphones that sit in her ears just at about the place where the outside part of the human ear canal would start. ((Not where the ear drums are – there’s a technical reason for this that I won’t go into here, but there are versions of binaural heads that do place the microphones right at the end of the ear canal.))

Her silicon pinnae are created from a CT scan of real human ears and these and her head create an aural ‘shadow’ which will match, in a generic way, the listening field of most humans. ((It probably has occurred to you that most humans have small differences in the shapes and sizes of their ears. Shouldn’t this mean that one person hears differently to another? Well, yes, that’s right. To make a really convincing binaural recording for yourself, you would ideally put microphones in your own ears, and record with your own pinnae and head shape. Indeed, there are methods for doing this. To me, it does seem rather sonically masturbatory, though…)) This means that a recording made with Binauralaura, will sound about as real as an audio recording can sound. ((There are numerous other impediments to capturing a sound recording that would appear as real as reality. Mostly this has to do with the way our brain constantly interacts with the environment – not just the sound itself – to modify what we hear. And, in fact, what we think we hear is nothing like what we physcially hear. This problem is never really likely to ba addressed with a mechanical recording system. Until we have some kind of direct ‘neural recorder’ you can never really expect to experience a sound recording that is like really hearing something.))

So if binaural recording is so magnificent, why isn’t it used for everything? Well, there is, of course, a catch. The binaural effect can only properly be discerned by wearing headphones. For the binaural image to remain coherent, the sound for one ear must not interfere with the sound for the other. Additionally, in order to avoid a doubling of the head and pinnae shadow (one gained from the recording, and then a second from the listener’s own head and pinnae), the reproduced sound needs to be played back as close to the listener’s ear canal entrance as possible. The most expedient method to do this is via headphones or earbuds. ((There are ways of achieving a serviceable binaural illusion in stereo speaker systems, but they are expensive, dependent on room acoustics, and require the listener to sit in a ‘sweet’ spot. Needless to say, all this is even less appealing than wearing headphones.)) Wearing headphones to properly hear binaural sound is, in fact, analogous to the requirement to wear glasses to see 3D images (indeed, binaural sound is often described as ‘3D’ or ‘holophonic’ sound).

I’ve had some opportunities to take Laura out for a bit of a test spin, and so far, the results are pretty nice. Here’s a short clip. Remember – wear headphones or earbuds to listen to it. One thing you will immediately notice is the clarity and and detail of the sound space. If your hearing is fair, you may also detect one of the extraordinary features of binaural sound – something you will not hear in a conventional stereophonic recording – and that is the ability to localise sound height. Have a listen now, and see why I went to all the trouble to build Binauralaura.

Download Laura Listens