Now that pretty much everything you can imagine has been turned into a movie monster, from the recombined pieces of corpses through cars, atmospheric moisture, dolls, dogs and dinosaurs, writer/director M. Night Shyamalan, director of such memorable moving pictures as, well, OK, only The Sixth Sense, has turned, for his latest effort, to that ultimate Creature of the Night: the larch. Yes folks, I’m giving away the plot. In his new film, The Happening, the trees did it.

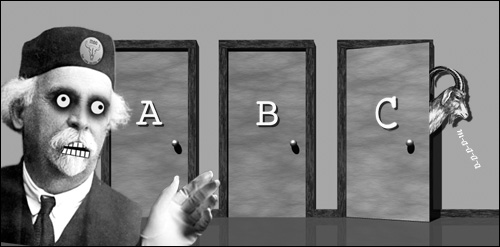

You will recall that some time ago I wrote that I wasn’t going to get into the habit of reviewing movies here on The Cow unless they were very very special movies…? Well, this is a very very special movie. Oh yes – ‘special’ in the way we used to be told to refer to the kids with learning disabilities in school.

Like Danny Boyle’s execrable Sunshine, Shyamalan’s The Happening commits the Number 1 Crime of science fiction; it is dumb. And, as if it’s trying to get one up on Sunshine, it also commits the Number 1 Crime of movies-in-general: it is boring. This film is dumb and boring. And annoying.† About twenty minutes into The Happening I contemplated emulating one of the film’s pheromone-addled humans and seeing if I could stuff enough popcorn up my nostrils to kill myself.

The story begins with a relatively intriguing stage-setting sequence in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park where a young woman begins babbling incoherently to a friend and then meticulously removes a chopstick-sized hairpin from her hair and inexplicably plunges it into her jugular. Other people around the park seem bewildered and disoriented, and screams echo from somewhere in the distance. Elsewhere in the city, Elliot Moore (Mark Wahlburg) a science teacher in a local high school, is enquiring of his class if they’ve ever heard of Bee Colony Collapse Disorder (a mysterious catastrophe that is, in actual fact, devastating honey bee colonies in the USA) and asking the students to put forth some explanations for this baffling phenomenon. The first kid to come up with a suggestion – “Some kind of disease?” – is in all probability right on the money, but this does not deter M. Night, via Marky Mark, from plunging headlong into the ridiculous.* Nope, Colony Collapse Disorder is nothing we could ever imagine: “It is,” pontificates Elliot weightily, “An Unexplained Act of Nature!™”

This scene, so very early in the piece, is an alarm bell that presages a series of inane pop-science clichés and baseless myths that will form the framework of the film. As Elliot strides around his classroom, attempting lamely to be Cool Mr Science Geek, all I could think was “Well, if American science teachers are anything like this, I now completely understand the success of the Intelligent Design movement in US schools”. It is true that Colony Collapse Disorder is perplexing and unexplained, but SO WHAT? Lots of things are perplexing and unexplained. Shyamalan quite obviously wants us to think that in this case it means that science is, somehow, inadequate for the job of providing any interpretation of CCD, and that is w-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o… SPOOKY!!!. Spare me.

It’s a real shame, because the premise of the film – that plants might evolve to react to humans as a threat, and consequently take measures to eliminate them – is actually reasonably original, The Day of the Triffids notwithstanding. It even has some slight basis in the natural world. It’s the kind of thing that a writer with more skill might have made into a decent yarn.

Meanwhile, in the picture’s only truly unsettling sequence, across town a bunch of construction workers start throwing themselves off the top of a building. It appears that the city is suffering some kind of mysterious pandemic (which in the paranoid US lexicon automatically means ‘an attack by terrorists’). It’s about here that the film turns rapidly brainless. And never recovers. News reports inform us that some kind of airborne agent is causing people in the city area to kill themselves. Early warning signs of contamination are confused behaviour and incoherent speech. The teachers in Elliot’s school are told to send their kids home and lay low. Elliot and his teacher pal Julian (John Leguizamo) decide to grab their families and head out of town.

We are next introduced to Elliot’s wife Alma (Zooey Deschanel) who appears from the very start to have been affected by the terrorist mind chemical, but as it turns out, that’s just her acting style and/or the witless script. Elliot calls by to collect her and they head off by train with Julian and his daughter Jess (Ashlyn Sanchez) in tow.

The train gets stopped in Nowhereseville USA, and after what seems like an interminable series of explanatory scenes, Elliot & Co manage to hitch a lift with a goofy guy and his wife who are some sort of horticulturalists. Goofy Guy is the first to offer the idea that maybe the source of the mysterious toxin which is affecting the humans comes from trees. On the way to a place that the group has perceived as ‘safe’ (Wha? Did anyone else understand how these fruitcakes decided this?) they stop by Goofy Guy’s greenhouse where we discover that he has a penchant for hotdogs (what the crap was that about?) and that he talks to his plants (and plays music to them).

“They respond to human voices!” he exclaims, rolling his buggy eyes around, “It’s a scientific fact!” And suddenly I see what he’s getting at – by now it is plain that the performances from the plants in this film are considerably less wooden than those of the actors, and this could be readily explained if you care to speculate that maybe M. Night Shyamalan spent more time on the set talking to the trees than to the people. Seriously. The dialogue and the acting in this picture must conspire to be some of the worst to hit the screen since Robot Monster or Plan Nine From Outer Space. Let me give you an example:

Elliot (talking about Goofy Guy’s theory that the trees are responsible): Maybe that guy was right…

Alma: What do you mean?

Elliot: I don’t know.

That’s the only one I can remember verbatim, but there are dozens of these kinds of clunkers. Mark Wahlburg, who is usually quite capable of turning in a reasonable performance, seems to spend most of the picture barely keeping the effect of the mind-altering plant toxins at bay. He stumbles around the countryside (and the film in general), as the ad hoc ‘leader’ of his little group, like a clueless boy scout about to fail his orienteering badge. In one memorable and quite absurd sequence he shouts over and over “Give me a second! Just give me a second! Why don’t you give me a second to think?! Just give me a second!!!”

All of which takes up more than a few seconds of his thinking time, but gives the audience plenty of time to think that they should have gone next door to see Kung Fu Panda. What Marky Mark comes up with in his thinking time is the brilliant strategy that the group should try and outrun the wind. I’m not kidding. This guy teaches science.

I won’t bore you with a blow-by-blow of the rest of the story.‡ And it truly is boring. Just imagine a confused road movie with panicked groups of people driving around the bucolic Pennsylvania landscape stumbling alternately across corpses and unhinged-people-who-will-eventually-become-corpses. When one victim throws himself under an industrial lawn-mower I was right there with him.

It’s hard to believe that a film can be quite this awful. With the vacuous substitution of scene changes and spectacle (in the form of shock-tactic suicides) for plot, and mawkish sentimentality for emotion, the movie plays to the dimmest of the dim. It mixes up scientific fact and the truth about natural events with hokum and nonsense in a mad mélange of glib throwaway hippie philosophy and post Cold War paranoid hysteria. It’s like Walt Whitman rewrote The Day of the Triffids after watching What the Bleep Do We Know? On crack. And, inexcusably these days for a science fiction film, it perpetuates the idea that scientists are either mad or bumbling, and that science itself is clueless and ineffectual. Or evil. These things are bad enough, but unbelievably, it’s even worse than just that. At times during the film Shyamalan seems not to know whether he is making a sci-fi thriller or a comedy. A bizarre scene with Elliot talking to a house plant is played, confusingly, first for tension then for laughs. In the cinema where I saw The Happening, the audience was laughing at, not with. Portmanteaus of people committing suicide in bizarre ways (a guy offering his limbs to lions in the zoo; the man lying in front of the lawn mower) are so blackly humourous that it’s hard to believe Shyamalan was oblivious to the effect they might have on the audience. If he was aware of this, one is forced to ask the question: “Why? What the heck is he getting at?” Sequences which I presume are intended to be symbolic and ‘meaningful’ (the Exhibition home with its fake sushi plates and prop wine glasses; the solitary ‘Earth Mother’ in her isolated homestead; the lame horror feint involving a rope-swing on a creaky branch) are flat and stupid and go nowhere.††

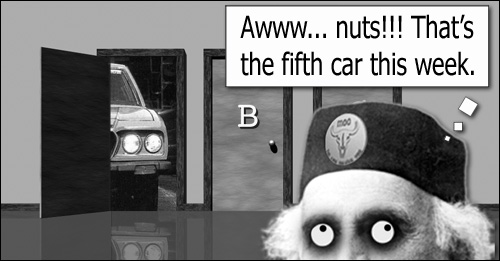

And the obligatory Shyamalan ‘twist’ ending, so obvious and soporific that it would have been rejected from the lamest episode of The Twilight Zone, is made even worse by ringing loud with a cinematic “Tsk tsk tsk: you humans don’t know nuthin’!”

As I said at the outset, M.Night Shyamalan’s The Happening is a movie with learning disabilities; it is to the science fiction oeuvre what Basil Fawlty is to the hospitality industry: an uncoordinated, unlikeable, nonsensical caricature that is a peerless example of what not to do if you at all concerned about pleasing your customers.

Did I mention it was dumb?

Right.

___________________________________________________________________________

*”Good theory Timmy,” says Marky Mark, metaphorically tousling the kid’s hair, “But it doesn’t explain why it’s happening everywhere at once!” No it doesn’t. That’s because, in all likelihood, Colony Collapse Disorder had already spread widely before it was noticed. It’s distinctly probable that it’s happening ‘everywhere at once’ in the same way as, say, AIDS is happening everywhere at once if you examine it right now. It does not mean that it didn’t start somewhere. Read about CCD here and get some understanding of how science is actually approaching this problem. (One is forced to conjecture that for a person writing about a phenomenon of nature and science and offering it up dressed in the robes of plausibility, M. Night Shyamalan was actually not terribly concerned with those pesky things like facts…)

†The film is peppered with scenes of people committing suicide in graphic and novel ways. It is the filmic equivalent of someone poking you every time you’re just about to doze off to a nice comfy sleep.

‡And there are SO many risible scenes to choose from: such as when Elliot confronts the train guards about why they’ve stopped in some remote town:

Train Guard: “Because we can’t go any further.”

Elliot: “But what are we supposed to do?”

Train Guard: “You’ll have to make your own way from here…”

Elliot (apoplectic): “Why are you giving me information one bit at a time!!”

Me (mentally screaming silently at the screen): “Because you only asked two things and besides are quite clearly mentally retarded”

Or the sequence when Elliot’s group hears gunshots from over the hill; the party they’ve just split from (after they’ve been told to stick together, I might add) has been affected by the toxins:

Alma (wincing as gunshots ring out, and we realise the people are shooting themselves): We can’t just stand here. We have to DO something!

Elliot stands dumbstruck, like a deer in the headlights.

Alma (hysterical): We have to DO something. We can’t just stand here like those people who watch an accident and do nothing!

Me (screaming silently at the screen): No you dumb bitch, you can’t! But you could act like people who’d made a rational appraisal of the situation and haul your asses out of there as fast as possible before the plant pheromones get to you too!!!

††If you want to see a movie about what an inexplicable event like this would be really like if it happened, try Michael Haneke’s Wolfzeit (The Time of the Wolf). I guarantee you won’t leave that film laughing.

___________________________________________________________________________