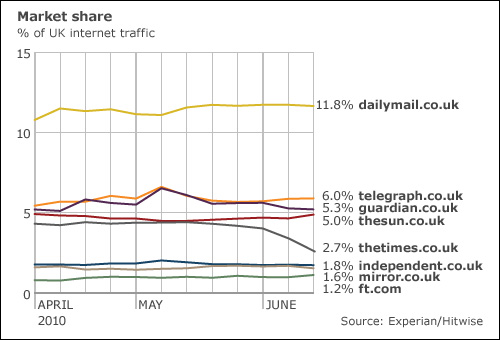

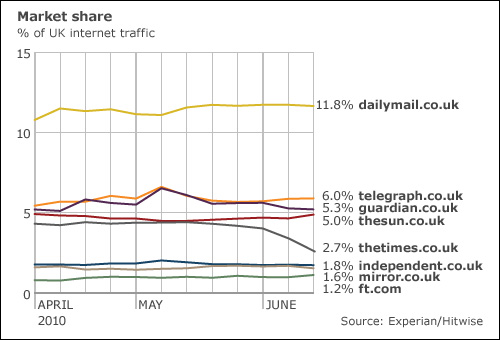

You will remember that a little while back we learned that Rupert Murdoch, using his needle-sharp insight into how people use the internet, stumbled on the notion that it would be a good idea to start charging visitors to read the online version of his flagship newspaper The Times. Consequently, the last month has seen The Times subscription gateway come into operation and readers have been asked to sign up (without paying) before they can get access to stories on The Times site. Here’s a graph that reflects the status of readership figures for various online UK newspapers since April.

Notice anything? And need I point out that this graph reflects only the sign-up process – no money has so far changed hands. Now, to my eye that looks like The Times online has lost nearly half its readers in a month. And the curve doesn’t look like it’s intending to taper off anytime soon, and that’s before we get to the point of actual money being forked out. ((Quite interestingly, the curve visibly trends downwards well before the subscription requirement kicked in. I surmise that this indicates people started abandoning the Times pretty much as soon as they heard that it was going to start charging money. If I was head honcho, I would have taken this as an extremely worrying omen.))

Rory Cellan-Jones, on his blog at the BBC, has speculated that The Times really only has to hang on to about 5% of its former readership ‘to have the champagne corks popping in Wapping’. I predict that the readership will fall right through that number and bottom out at nearly zero. Rory puts his finger right on it in his post:

My suspicion is that the main problem with this experiment is what I’d call friction. Web users have got used to clicking simply from one page to another without hindrance. Any element of friction – the aggravation of having to pay or just log in – acts as an incentive to head elsewhere in a hurry. I tried an experiment this morning, posting a link on Twitter to an article by the very funny Times columnist Caitlin Moran. Plenty of people clicked on the link – but when they were taken directly to the Times pay-station, they all appear to have left without paying.

To anyone who’s been looking at web media for any length of time, this is truly a no-brainer. Why would you bother? Rupert is pinning all his hopes on one single idea: that people care enough about the quality of the journalism (and whatever else The Times has to offer) to pay for it. ((It also breaks one of the most important pieces of functionality of the web, and very few of the Old Guard understand this because it is such an alien concept to them: the ability to cross-link. Anyone who writes a blog (or anything written specifically for online diffusion) understands automatically how powerful a utility this is. The web is a ‘web’ because it builds itself on connectivity. If I want to write something on Tetherd Cow I can easily bolster my story with examples, references and asides that anyone can check instantly. But there’s NO WAY I can do that with the Times any longer. If I cross-linked to an article in the Times, my readers would simply behave as those in Cellan_Jones experiment, above. Murdoch’s idea is fundamentally destructive to the very foundations of the internet. Where we see the awesome power of the building up of information structures, he wants to create cloistered communities that he can control. This, in my opinion, is what will ruin him. He does not grok the net.))

Rupert, I’m sorry to say that the 21st Century is going to give you a bigger ass-walloping than you ever thought possible.

Let me explain it in a way that even Mr Murdoch might understand. Are you sitting comfortably? Very well, let’s begin.

Once upon a time, when horses and buggies were the fastest forms of transport and people cleaned chimneys by crawling up them with big brooms, accounts of what was happening in ‘the world’ started to get circulated via a system called ‘the newspaper‘. The newspaper gathered up a collection of what its publishers deemed the most relevant and interesting bits of news and gossip of the moment, and then distributed them to the community. The newspaper was a marvellous idea for its time, but, for all its charm and utility it did have some limitations: it was largely a local phenomenon, it cost money to make and deliver to the people who wanted it, and it had a kind of inbuilt time delay (if news happened, you had to wait till the next newspaper was made in order to know about it). But because it was a physical object, and it was a convenient way of learning about the latest goings-on in the world, people were prepared to pay some small amount of money to take possession of their daily newspaper. Plus, you could wrap fish & chips in it when you’d finished reading it. (It also had another limitation, but one that few people were aware of at the time: it was a one way street. That is, the newspaper could tell you things, but you could not reply to those things, nor enquire after their veracity.)

Eventually, after a few decades of news distribution of this form, a few cunning people realised that if they could gain control of the newspaper business on a large enough scale, they could earn themselves quite a bit of money. And so newspaper tycoons came into existence. The object of being a newspaper tycoon was to gather up as many small local newspapers as you could find, and either put them out of business, or amalgamate them into your empire. This concept made a small number of crafty men (for they were ALL men) very wealthy indeed. It had the added bonus, for those men, of giving them extraordinary political power, because after all, they controlled what people knew about the world. This state of affairs existed for the better part of a century, with the newspapers becoming more and more ubiquitous and the newspaper men more and more wealthy and more and more powerful.

But then, late in the 20th century, a completely unexpected thing happened – a wonderful piece of technology called ‘the internet‘ came along. The internet was really nothing more than a way in which everyone on the planet could easily and instantly talk to everybody else, no matter how geographically separated they were. It was a simple but powerful idea. And the more people who understood this idea, the more powerful it became. Before anybody really even knew what was happening the internet became connected to all kinds of places across the whole world, and people happily discovered that news and gossip and all kinds of other information could now be exchanged rapidly and for free. People liked that! And the internet was unlike the newspaper in one very important way: nobody ‘owned’ it and nobody could own it. ((You can bet your humidified Havana cigar that there are those who, if they’d known how it was going to turn out, would have moved heaven and earth to have gained control of it…))

So who do you think were the most unhappy about this state of affairs? That’s right – the newspaper tycoons. They were VERY VERY upset, indeed. People were talking to each other and learning about their world for free! What a terrible, terrible thing!

Thanks to their innate carnivorous business instincts, though, the tycoons became aware very rapidly that this ‘internet’ was something quite big and important, and they could see that people had taken to it like ducks to water. Unfortunately they could only see this through spectacles that had little dollar signs embossed all across the lenses, and so their vision was not very clear. The first thing they did was to nab themselves some real estate on this internet thingy. After all, it was FREE, what did they have to lose? Of course, the people who were already on the internet were happy to see their old friends from the newspaper business there and started visiting these new sites from the old guard – but they didn’t just hang out at one newspaper… oh no! They were now reading six or seven or maybe even ten newspapers, and not just newspapers from their home town either! And not only that, they were getting news from sites that weren’t actually newspaper sites but had news anyway, like blogs and ezines and social networks and all manner of other strange ideas! All for free!

The newspaper tycoons weren’t used to the concept of ‘free’. It was not something that was in their world view. When they said the word ‘free’, as they sometimes did, they meant ‘we’re giving you a nice little morsel but it has a hook hidden inside it’. The concept of ‘free’ as in ‘you can get it with no strings attached’ was as alien to the newspaper tycoons as was the idea of travelling economy class, so they looked upon what was happening on the Internet with a great deal of bewilderment and frustration. All these people were here doing stuff and hanging around but the tycoons couldn’t figure out a way to make money from it! How they hated that! How dare people amuse themselves!

So instead of making some kind of effort to understand what was going on with the Internet, as some of their cleverer and less mercenary colleagues did, the tycoons contrived to do the least effective thing possible: they attempted to make the Internet play by their Old Rules. Unfortunately, the people using the internet could see immediately that the Old Rules really suited no-one except the tycoons. The only option open to the tycoons now was to try and make their Old Way look more enticing than all the New Things the Internet was offering. They did this mostly by telling everyone how TERRIBLE the New Way was and how much BETTER the Old Way was. They said this loudly and often.

‘If you continue to get your news for free,’ they cried ‘You’ll only get TERRIBLE quality news. WE are the keepers of GOOD quality news!’

Unfortunately, the people using the internet already knew that this was a stupid and desperate tactic. They knew that not only was the news from the New internet way just as good (and sometimes even better) than the Old newspaper way, but that the Old newspaper way gave them TERRIBLE quality news as often as not too!

In spite of this obvious failing, the tycoons quite idiotically convinced themselves their argument was good enough to charge money for their Old News, just like they used to do when the world was all nice and simple, before smoking tobacco caused cancer and when it was perfectly acceptable to feast on endangered species of quail and unsustainable caviar stocks. And so they said to the Internet people:

‘Now we want you to PAY for our Old Ideas, even though we have made exactly NO CONTRIBUTION to this new way of doing things…’

Well, we’ll have to leave our story there for the moment, because the last words have not quite been written. I suggest that ‘Happily ever after’ is not on the cards for those old newspaper tycoons, though. They are facing the end of their dynasty and they stand, as emperors have often done, bewildered in the empty halls of their palaces while the revolutionaries hammer at the gates.

Will Rupert get his 5% faithful? Will the champagne corks be popping in Wapping? Will the line on that graph level out before it hits sea level? Six months is about what I think it will take to give us the ending to this story.