Thu 25 Aug 2005

Resonance

Posted by anaglyph under Brushes With Fame, Geek, Music, Travel, Work

[7] Comments

A Long Story Involving Music, Death, Snow and Coincidence

One Saturday morning in late 1991 I was woken from a deep sleep by the most ethereal of sounds. It was a perfect pure human voice singing Rachmaninoff’s ‘Vocalise’… no wait a minute, it’s wasn’t a voice, it was… a violin… and yet…

I came into full consciousness too late to catch anything much of the back-announce, except for the name of the artist: Clara Rockmore. It was enough to chase down the recording. It turned out that the sound I heard wasn’t a voice, or a violin, but that most enigmatic and fascinating of electronic instruments, the theremin.

As a teenager I had a fleeting interest in theremins, and even tried to build one out of an old electronics kit I hacked for the purpose. It wasn’t too successful, and I really didn’t have the chops to do it properly. Besides, I had bigger fish to fry; I had become obsessed with the gadget that had newly arrived in the local music shop – a music ‘synthesizer’ called a MiniMoog.

Long story short: MiniMoog → rock & roll band → sound & music for school plays → film school → my own film company → lying in bed listening to Clara Rockmore effortlessly play the theremin, perhaps one of the most difficult-to-master instruments of all time.

I tracked down that recording of ‘Vocalise’ and discovered to my mild surprise that it had been produced by Robert Moog, inventor of that MiniMoog that had set me on my career path, and a man considered by many to be The Father of Electronic Music. As it turned out, Bob’s own career was directly related to his interest in, and manufacture of theremins as a teenager.

The comprehensive liner notes with the CD outlined the amazing story of Lev Sergeyevich Termen (Leon Theremin) and the invention of his extraordinary electronic musical instrument. That’s a different long story, and way too fascinating for brevity, but you should read it on Wikipedia sometime. What was most astonishing to me was that, at the time, Leon Theremin was still alive, at the grand old age of 95. And, as far as I knew, there was no filmic document of this important man and his contribution to music and technology.

I was very well placed to set up such a documentary, and I immediately started collecting information. I got in contact with a number of people and soon enough with a chap at Berkeley who told me in an email “I think someone’s already making a movie – you should speak to Bob Moog”

And I did. Yes, said Bob, a fellow called Steven Martin had almost completed his film Theremin: An Electronic Odyssey, after a difficult three year process. In keeping with my inept abilities as a surfer I had sensed the wave coming too late, and Steven Martin was already riding it to shore. Tarnation.

I had a number of very nice conversations with Bob though, so I didn’t feel too bad about losing the doco, him being a hero of mine and all. I also discovered that through his company Big Briar (now Moog Music), Bob was making theremins again. It was too good an opportunity to miss and I browsed their catalogue and arranged for Big Briar to make for me one of their beautiful cherry wood Model 91Cs.

As fate would have it, the proposed completion date for my theremin would see me in North Carolina where I was to meet up with my business partner at the time, Alex, on the set of the new film he was directing, the soon-to-become ill-fated The Crow.

Big Briar/Moog Music is located in Leicester in NC, and it was a simple matter to arrange a slight detour at the end of my trip to collect my theremin in person. More importantly of course it would allow me the exciting opportunity to meet and shake hands with the man whose name was synonymous with electronic music.

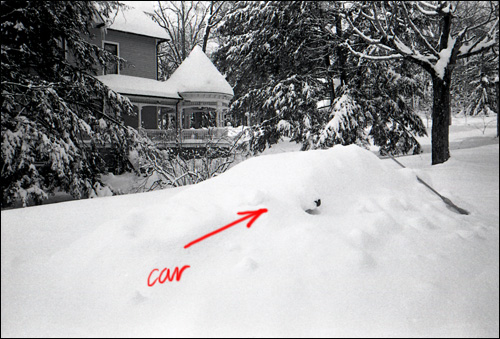

It was never to happen. 1993 saw one of the worst storms to ever hit the east coast of the US, with North Carolina copping one of the biggest snowfalls in its history. The day before, I arrived with my travelling companions in Asheville NC, about a twenty minute trip to Leicester. The fairy-tale sprinkling of snow that started on that night was a big novelty for us Australians. “How very Winter Wonderland!” we cried, as we grappled with the concept of driving in treacherously icy conditions and on the wrong side of the road. It became something less of a novelty the next day when we had to dig down through several feet of snow to our rental cars. That was just to get our luggage. Those cars weren’t going nowhere. Neither was anything else in Asheville.

We stuck it out in Asheville for three days but things weren’t getting better in a hurry. Leicester was completely cut off from the world, and any possibility of getting there and back in time to meet our flight back to Oz was remote. We had no choice but to grab the first local flight out of Asheville (after a terrifying drive-cum-slalom in a taxi to the airport) and head back to a country where there isn’t ever much snow. Certainly not enough to bury cars.

My theremin was shipped to me not long after, and Bob phoned several times to chat, and make sure everything had arrived in good condition.

Steven Martin’s documentary was completed in 1993. It was an insightful and moving account of the story of the theremin. Lev Sergeyevich Termen died not long after the film’s release at the age of 97. Bob Moog sent me an email on that day. It said:

I thought you would like to know that Lev Termen died today, at the age of 97. Lately, he has been working on a device to reverse the aging process. Sadly for all of us, he was not able to finish that work.

I was very saddened to hear that Bob Moog himself died last Sunday. The enormous grief in the electronic music community can be felt on the Moog Music site, and on the Caring Bridge site, where thousands of people have left their condolences and sympathies, as well as thoughts and reminiscences about Dr Moog.

Unlike Leon Theremin, Bob Moog runs little risk of being forgotten. His legacy to the musical world is imprinted so strongly that the word ‘moog’ is almost a generic term for an analog synthesizer. And now, his instruments have been created virtually, as software emulations, for a whole new generation of sound-makers to discover.

So, at the end of this lengthy post, I would like to bid a personal farewell to Dr Robert Moog, the great man who I almost met. So long Bob. I feel I knew you well enough to call you a friend. Forgive me if that’s presumptuous. I’m not so presumptuous as to speculate on whether there is a heaven or not, but in my mind’s eye I cannot help but see you ascending a glittering stairway to some such place, dressed in a magnificent white tux, and accompanied, in a manner befitting your stature, by a chorus of a thousand angels playing perfect theremin.

7 Responses to “ Resonance ”

Trackbacks & Pingbacks:

-

[…] You can read about how I came by this beautiful instrument here. […]

Did you find out more at the time Termen died about the anti-ageing device, Peter?

I just googled it, and apparently Larry Ellison (CEO of Oracle) was involved in funding, but that’s as much as I could find out.

A quietly moving story – thanks for sharing.

No, I know nothing more about Lev Sergeyevich’s anti-aging work. I’m impressed you even found the Larry Ellison link. In case it sounds like a preposterous concept, I should say that aside from making his theremin a scant year after it was technically even possible (the electronic valve was invented in 1917 and the first theremin was made in 1918) Termen was the inventor of the remote listening device for the KGB and the prototypes for what would become the modern burglar alarm.

This all at a time when even the concepts for such things were non-existant.

What a great story! Thanks, you’ve brightened my day.

I have a huge lump in my throat after reading this lovely tribute. Thank you so much for putting this all down to share with us all. Also, I really like reading through your site and have added Tetherd Cow to my blogroll. Great to find another kindred soul “out there”.

Thanks wp. It is sometimes the people we meet in fleeting contact that have the biggest effects on our lives.

Great tribute, beautifully written.