Sun 5 Aug 2007

On Reflection IV

Posted by anaglyph under 7 Famous Mirrors

[4] Comments

7 Famous Mirrors (cont)

•5: The Hubble Space Telescope Mirror

Dutch spectacle maker Hans Lipperhey is credited with the invention of the telescope. Or at the very least, he is acknowledged to be the first person to try to put a patent on one. I read about Lipperhey a few years ago and was quite surprised to hear about him – like many people of my age I was taught in school that the first telescope was invented by Galileo Galilei. It was Galileo who made the first extensive annotated observations with a telescope, of that there is no doubt, but he must take his place in the queue when it comes to credit for the invention of that most marvellous of humankind’s augmentations.

Even Lipperhey was standing on the shoulders of giants. By now, it will not surprise you at all when I tell you that it was Leonardo da Vinci who, among his cornucopia of other spectacular ideas, first speculated on the possibility of magnifying the heavens, not with lenses, but with mirrors. Leonardo can wear the mantle of genius without any dispute.

In his notebooks, Leonardo writes about:

…making glasses to see the Moon enlarged… and advises would-be astronomers that …in order to observe the nature of the planets, open the roof and bring the image of a single planet onto the base of a concave mirror. The image of the planet reflected by the base will show the surface of the planet much magnified.

He has in fact outlined a principle that we would today find familiar as a reflecting telescope. Lipperhey and Galileo were viewing the night sky with refracting telescopes. Mirrors vs lenses, in other words.

Leonardo’s idea for magnifying the heavens is in spirit pretty much exactly like our miroir du jour – the six foot reflector installed at the heart of the Hubble Space Telescope.

The HST sits in Earth orbit far above the atmospheric haze that is our atmosphere and returns to us the most extraordinary images of the universe that we have ever seen. The Hubble Telescope optics consist of a fairly simple arrangement of mirrors called a Ritchey-Chretien Cassegrain system. Basically, a curved mirror not unlike the one Leonardo described, is reflected by a flatter convex mirror into the telescope’s electronic detectors.

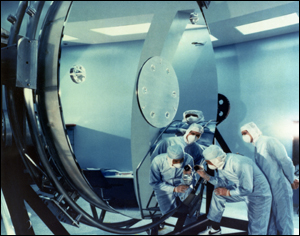

For the crispest, most efficient management of the faint light of distant stars and galaxies, it is crucial that these two mirrors are made to the most exacting specifications. Specifically, the technical requirements for the main mirror are that it should not deviate from a perfect curve by 1/800,000th of an inch.

One can only imagine the swear words that resounded in the NASA control rooms when it was discovered, shortly after its deployment in 1990, that the Hubble Telescope had a significant fault in its main mirror. The mirror’s manufacturer, the Perkin-Elmer Corporation, had made some critical errors during the 10 year process of grinding and polishing the mirror, which resulted in serious degradation of the images returned from the telescope. The problem was eventually rectified, first by using computer algorithms to compensate for the distortion added by the mirror, and then by applying corrective optics in front of the mirrors.

All screw-ups notwithstanding, the mirror in the Hubble Space Telescope can definitely take its place among the most famous of humankind’s mirrors. The Hubble now approaches the end of its useful life, as NASA prepares for the installation of the James Webb Space Telescope in 2013. The JWST boasts a mirror more than three times the size of the Hubble mirror, and there is no doubt at all that it will show us sights of which we have never even dreamed.

And most amazingly of all, it will still use the very same principle outlined by Leonardo so many centuries ago.

That Leonardo!

Is there anything he DINT think of?

I hope he’s a better artist than Michelangelo in that arena.

I feel what I think of as child-like wonder when I see Hubble images. Hope I’m still around (and not overly enfeebled) when the next generation views begin to unfold.

The James Webb telescope will see mostly into the infra-red which has turned out to be a more efficient way to view the distant universe than visible light. Nevertheless, it still uses a concave reflector to gather this infra-red light, and it promises to show us very spectacular things…